Overall Water quality

The water situation at Kawainui is constantly changing as a result of rapid, frequent, or extreme changes that occur outside of the stream. The amount of water left in the open marsh (which is directly dependent on rainfall runoff), the health of the ecosystem and respective quality and quantity of the water inflowing from the Maunawili Stream (the marsh's largest natural water source), and the appearance of the saturated land around the marsh are all subject to fluctuation.

As the sea level rises it has a direct correlation with the level of the marsh. This means that much more land has been "submerged" and is now no longer solid ground. When more land is submerged, the size of the marsh typically increases, but with the amount of encroaching vegetation surrounding the pond today, this subversive effect has not done much to preserve the area of the central portion of the pond.

The small amount of water left in the marsh shows evidence of abundant micro-sediment presence as a result of it's origins in and journey from outlying streams and orographic rainfall cycles. (5)

As the sea level rises it has a direct correlation with the level of the marsh. This means that much more land has been "submerged" and is now no longer solid ground. When more land is submerged, the size of the marsh typically increases, but with the amount of encroaching vegetation surrounding the pond today, this subversive effect has not done much to preserve the area of the central portion of the pond.

The small amount of water left in the marsh shows evidence of abundant micro-sediment presence as a result of it's origins in and journey from outlying streams and orographic rainfall cycles. (5)

Water Level

|

According to data collected from a previous research, the island's wetland percentage dropped from pre-settlement to current. Specifically, the wetland area decreased from about 160 km² before settlers arrived, to 60 km² in more recent times. This is a huge drop in the water quantity in Hawaiʻi overall, which does relate significantly to Kawainui as well. This also coincides with other research found regarding the water quantity of the marsh. After 1966, rapid urbanization of the Kailua watershed led to soil erosion and increased basin sedimentation. This steadily decreased the volume of the basin, consequently the water storage capacity. Decreased water levels pose a threat to the complex ecosystems inhabiting the marsh. (9) |

|

Runoff

The marsh acts as a sediment trap for runoff entering from the streams of the Kailua watershed. This keeps harmful nutrients and pollutants out of Kailua Bay, which is vital for the health of coral reefs as sediment can smother coral and pollutants can decrease water quality. The marsh also acts as an important basin for freshwater runoff. The marsh stores up to 9.5 million gallons of water per day, and acts as a flood control basin. However, urbanization of the area has lead to a decrease in the amount of water the marsh is able to handle. Discharging partially treated nutrient rich wastewater during the 1960s has lead to the rapid growth of exotic vegetation, which has clogged waterways, further decreasing the water flow in the marsh. This has all lead to a higher risk of flooding in the Kailua area, and is detrimental to the health of the marsh and surrounding waters. (12)

Inorganic Material & Pollution

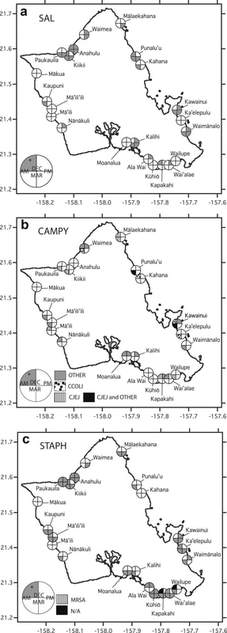

Testing in 2011 has shown that the stream water of Kawainui has at least five different bacterial pathogens at varying times of the year.

22 streams were tested, and Kawainui was one of the 12 that contained all five of these pathogens.

The pathogens found were Salmonella, Campylobacter, Staphylococcus aureus, Vibrio vulnificus, and V. parahaemolyticus. (3)

(Fig. 1. Presence/absence of a) Salmonella, b) Campylobacter, and c) Staphylococcus aureus in 22 O’ahu coastal streams (shaded = present, white = absent) by time of day (AM/PM) and season (DEC/MAR). Circles denote DEC with top half and MAR samples with bottom half. AM presence is on the left and PM presence is on the right. For CAMPY (1b), positive C. jejuni are lines, positive C. coli are dots, positive C. jejuni and other CAMPY are black, while other CAMPY are shaded. For STAPH (1c), positive MRSA in March is indicated by stripes while STAPH analyses not completed are black in that part of the circle.) (3)

22 streams were tested, and Kawainui was one of the 12 that contained all five of these pathogens.

The pathogens found were Salmonella, Campylobacter, Staphylococcus aureus, Vibrio vulnificus, and V. parahaemolyticus. (3)

(Fig. 1. Presence/absence of a) Salmonella, b) Campylobacter, and c) Staphylococcus aureus in 22 O’ahu coastal streams (shaded = present, white = absent) by time of day (AM/PM) and season (DEC/MAR). Circles denote DEC with top half and MAR samples with bottom half. AM presence is on the left and PM presence is on the right. For CAMPY (1b), positive C. jejuni are lines, positive C. coli are dots, positive C. jejuni and other CAMPY are black, while other CAMPY are shaded. For STAPH (1c), positive MRSA in March is indicated by stripes while STAPH analyses not completed are black in that part of the circle.) (3)

Scope of the land

|

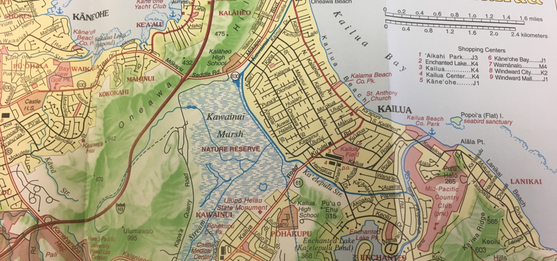

The map to the right shows the water flow from the mountains, down to Kawainui marsh, and into the ocean. This is closely tied to what Hawaiians previously understood about the waters of Kane. They knew that the water collected in the mountain tops from the orographic rain, and flowed past the forests and onto the ground to provide freshwater to the people. This flow from the mountains to the sea must be regulated in order to ensure adequate movement across the marsh. The marsh must be maintained to prevent flooding in the residential areas, which are very close to the edge of the marsh.

|

Map of Oʻahu, the gathering place: full color topographic / cartography by James A. Bier (10)

|

human impact: Past and present

(1Biogeochemical studies on sedimentary changes reveal the direct influence of humans through time. It has been found that impact derived from post-European contact due to land clearing and increased agricultural practices; however, new findings show impact from pre-European contact. There was a big change in sedimentation rate between 1690 and 1760, which researchers termed the "peak impact time". This coincides with the timing of the fishponds, which could potentially indicate that impact began earlier than previously understood. (1)

(8Recent human impact with the water flow of the marsh, is the development of the levee. This was a part of the Kawainui Marsh flood control project, and included construction of canals which were thousands of feet long. The levee was built to increase the flood water storage capacity of the marsh; however, it has been found that such changes cut off natural water flow from Kawainui marsh to the Kawainui stream. This caused a built up of stagnant waters. When water is stagnant and cannot flow to the streams and to the ocean, it endangers the aquatic life and the birds. It also decreases the overall health of the marsh. (8)

Restoration Efforts

In response to the aforementioned issues regarding pollution, run-off, human involvement and relation, etc., restoration efforts and groups of volunteers and concerned citizens have rallied in support of the ʻĀina. The hope of so many is to restore the Wai (water) cycles (AKA the process of orographic rainfall) to a natural rhythm in which the Hawaiian land and its people can someday return to a relationship of co-dependency, cohesion, and symbiosis.

An example of this can be seen in the image to the right. This sign was created by concerned Hawaiian citizens/those with leverage in the state government in regards to the Kawainui actions in Kailua, Oʻahu. In spite of discouraging laws and actions on behalf of the government, visitors to the state, etc., there are still many citizens working together to save the highly-revered land effected by the Kawainui legislative processes. (6)

An example of this can be seen in the image to the right. This sign was created by concerned Hawaiian citizens/those with leverage in the state government in regards to the Kawainui actions in Kailua, Oʻahu. In spite of discouraging laws and actions on behalf of the government, visitors to the state, etc., there are still many citizens working together to save the highly-revered land effected by the Kawainui legislative processes. (6)

A portion of the marsh used to be regularly cleared of encroaching vegetation that may disturb the wetlands by local ahupuaʻa residents, and drainage from the marsh redirected to other lands to aid in food/other resource production.

However this is no longer a regular practice and the vegetation now grows freely, which has largely committed to the shrinking of the pond into the Kawainui marsh that we know today. (5)

However this is no longer a regular practice and the vegetation now grows freely, which has largely committed to the shrinking of the pond into the Kawainui marsh that we know today. (5)

Community Perspectives

|

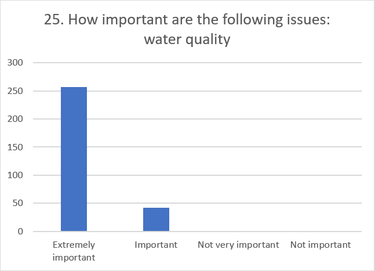

Many community members voiced their concerns over the water quality and quantity of the marsh. The following are the specific problems that were brought up:

|

|

Citations

1. Anderson, Brittany & Zhang, Li & Wang, Huining & Lu, Tianyi & Horgen, F. David & Culliney, John & Fang, Jiasong. "Sedimentary Carbon and Nitrogen Dynamics Reveal Impact of Human Land-Use Change on Kawainui Marsh, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i." Pacific Science, vol. 71 no. 1, 2017, pp. 17-27. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/646005.

2. "Kawainui-Hāmākua Master Plan Community Survey." Survey. 18 April 2018.

3. Viau, Emily J., et al. “Bacterial Pathogens in Hawaiian Coastal Streams—Associations with Fecal Indicators, Land Cover, and Water Quality.” Water Research, vol. 45, no. 11, 2011, pp. 3279–3290., doi:10.1016/j.watres.2011.03.033.

4.“HB1218 HD1.DOC.” Hawaii State Legislature, www.capitol.hawaii.gov/session2018/bills/HB1218_HD1_.HTM.

5. “Koolaupoko Regional Ecosystems - Kawai Nui Marsh.” Kailua Ahupua'a / Kailua Watershed Homepage - Windward Watershed Web Ring, Oahu, Hawaiian Islands, 30 Mar. 2011, www.koolau.net/Kawai_Nui_2.html.

6. “Wetlands Restoration at Kawainui and Hamakua Marshes.” Hawaiian Forest, hawaiianforest.com/wp/wetlands-restoration-at-kawainui-and-hamakua-marshes/.

7. “Oneawa Channel and Kawai Nui Levee Descriptions.” Kailua Ahupua'a / Kailua Watershed Homepage - Windward Watershed Web Ring, Oahu, Hawaiian Islands, KBAC, www.koolau.net/Oneawa.html.

8. “Going with the Flow: Oceanit Study Aims to Improve Water Quality at Kawai Nui Marsh.” Oceanit, 6 Apr. 2017, www.oceanit.com/news/going-with-the-flow-oceanit-study-aims-to-improve-water-quality-at-kawai-nui-marsh.

9. “20th Century Maps, Photos, Charts.” KAWAINUI, www.kawainui.org/20th-century-maps-photos-charts.html.

10. Bier, James Allen. Map of Oʻahu, the gathering place: full color topographic / cartography by James A. Bier. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2007. Retrieved from: chantelle808.wixsite.com/kawainuimarsh107a.

11. 20th Century Photos, Charts and Maps: https://www.kawainui.org/20th-century-maps-photos-charts.html

12.Frank, Kiana. “The Effect of Residential and Agricultural Runoff on the Microbiology of a Hawaiian Ahupuaa.” Water Environment Research, vol. 77, no. 7, Jan. 2005, pp. 2988–2995., doi:10.2175/106143005x73866.